Chữ Nôm - A Creative mark of the Vietnamese People

Chữ Nôm constitutes a salient phenomenon in the historical development of Vietnamese culture. In essence, it is a script that appropriated the graphic forms and principles of character construction from the Chinese writing system to transcribe the Vietnamese language—yet in doing so it embodied a remarkable degree of indigenous creativity.

A question long debated by scholars is: when did Chữ Nôm first emerge? Some suggest that as early as the beginning of the Common Era, with the introduction of Chinese script into Vietnam, isolated “Nôm” graphs were created to represent local toponyms, personal names, and native products, inserted sporadically into Chinese texts. However, this does not imply that Nôm, as a coherent logophonetic system for Vietnamese, was already in existence at that time. The transformation from scattered, provisional characters to a structured and functional script was a protracted process. On the basis of extant research, it is now generally accepted that by the Trần dynasty (13th century), Nôm had achieved the status of a recognizable writing system with the capacity for independent use.

Familiar Yet Unfamiliar

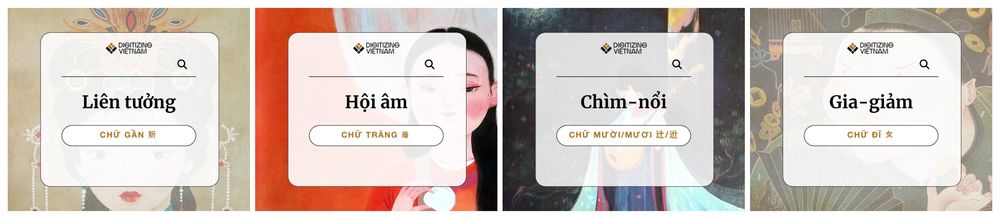

Readers literate in Chinese often assume, at first glance, that they can easily comprehend a Nôm text. Closer examination, however, reveals their surprise at finding it largely unintelligible. This paradox stems from the fact that while Nôm characters retain the outward form of Chinese graphs, their modes of construction are uniquely innovative. Beyond conventional methods such as semantic–phonetic compounding, Nôm also employs associative principles, semantic linkages, and what scholars have termed “submerged–emergent” structures, which defy the expectations of readers trained only in Chinese.

The Structure of Chữ Nôm – Some ‘Keys’ to Decipherment

Scholarly inquiry into the structure of Nôm has yielded various classificatory schemata. Rather than rehearse these in detail, it is useful to underscore several critical insights.

Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng distinguishes between “Nôm giả tá”—instances where Chinese characters were borrowed wholesale or with only minor phonetic shifts, which need not concern structural analysis—and those instances where characters were adapted or created with modification. In such cases, structural analysis becomes essential. Examples include reduction, as in the character Một 殳, traced to 没 but with a component elided; and augmentation, as in Đĩ 𡚦, created by adding a dot to the graph 女 (“woman”).

Even more complex are characters created through phonetic amalgamation. Such characters have no precedent in Chinese and epitomize Nôm’s distinctiveness. As Nguyễn Quang Hồng notes, these include:

Phonetic compounds (hội âm): characters combining two phonetic elements, e.g. Trăng/Giăng < blăng 𢁋 (巴 ba + 陵 lăng), Trước 𨎟 < klươc (略 lược + 車 cư), reflecting the preservation of complex consonant clusters (bl, ml, tl) in Vietnamese prior to the seventeenth century.

Radical assignment by associative linkage: some characters exhibit radicals that seem semantically incongruous unless viewed relationally. For example, Lỡ (𧾷+呂) in the line “Tối tăm lỡ bước đến đây” (Lục Vân Tiên) gains explanatory force only when juxtaposed with the following character Bước 𨀈 (𧾷+北). Similarly, the use of the “shell” radical 貝 in Gần 𧵆 becomes intelligible only in its semantic pairing with Xa 賒, which itself carries the radical 貝.

Submerged–emergent structures: certain characters conceal part of their phonetic basis, leaving visible only partial indicators. For instance, variants of Mười/Mươi (𨒒, 辻, 𨑮) contain the radical ⻍ (“walk”), traceable to the fuller phonetic base 迈 (mại). Here, the overt (emergent) structure coexists with an implicit (submerged) structure, a duality crucial for understanding the logic of Nôm character formation.

Such phenomena reveal both the structural “instability” of Chữ Nôm and, at the same time, the ingenuity, adaptability, and resourcefulness of its users. By situating these characters within broader networks of phonetic, semantic, and contextual associations, one gains access to the interpretive keys necessary for engaging with Nôm texts.

Thus, the study of Chữ Nôm not only illuminates the inventive capacities of Vietnamese literati but also demonstrates how local cultural agency appropriated and transformed foreign models into a distinctive script responsive to the phonological and semantic demands of the Vietnamese language.

(Based on “Some Issues and Aspects of the Study of Nôm” in the collected volume Language. Script. Literature by Professor Nguyễn Quang Hồng)