Phillips Library digitizes Vietnamese dictionaries

The Phillips Library has digitized two early-19th-century Vietnamese dictionaries that illuminate an overlooked chapter of U.S.–Vietnam scholarly contact. In 1819, U.S. Navy lieutenant John White received the manuscripts in Saigon from Italian priest Joseph Morrone and deposited them with the East India Marine Society (precursor to the Peabody Essex Museum). Peter Stephen Du Ponceau later borrowed and published them in 1838 alongside his Dissertation on the Nature and Character of the Chinese Writing System, helping ignite a trans-Atlantic debate about Asian languages and giving the United States an early role in introducing Vietnamese to Western readers.

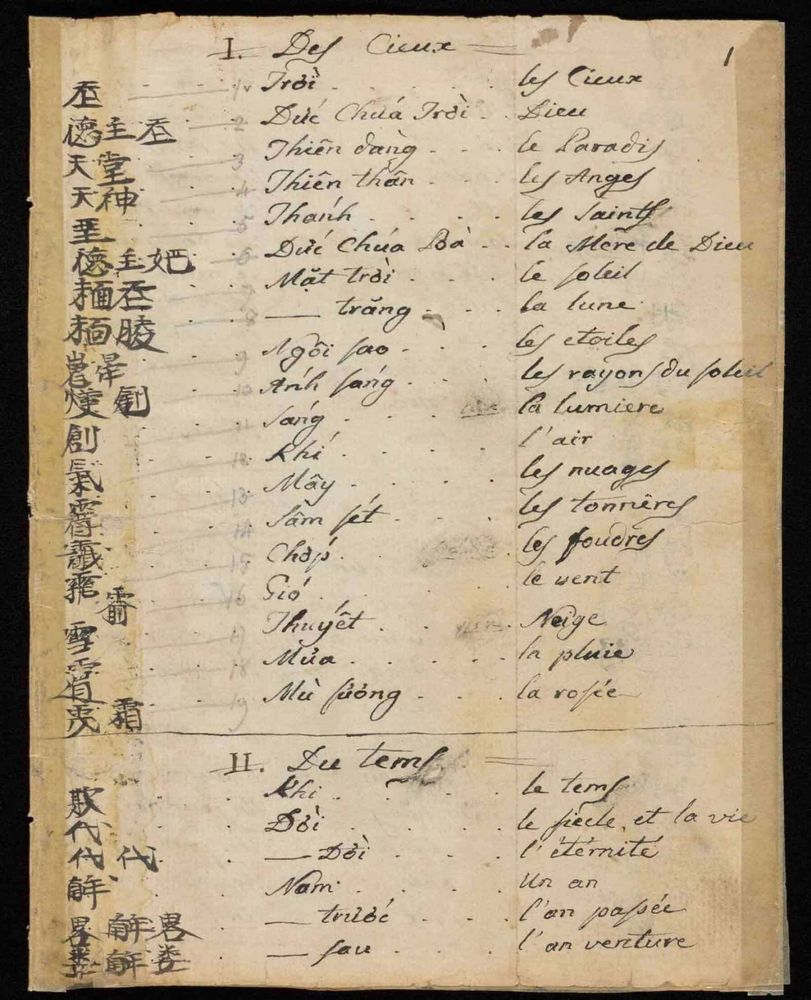

Digitization reveals what the printed edition obscured: the manuscripts preserve chữ Nôm (Vietnamese demotic characters), Romanized Vietnamese, users’ annotations, and missionary teaching traces. The first work, Lexicon Cochin-Sinense Latinum ad usum missionarium—a Latin-Vietnamese dictionary long copied and customized by newcomers—runs 139 pages, with Romanized headwords, a binding made from calligraphy practice sheets, and a loose page recording the Lord’s Prayer and Hail Mary in Vietnamese. These tools served Catholic proselytization, yet also mediated exchange the other way: when speech failed, a Vietnamese official initiated written communication with White’s crew in Latin (“Quid interrogas?”). Du Ponceau used evidence like Nôm to argue against the idea of Chinese as a universal ideographic script.

The second manuscript, Vocabulaire domestique Cochinchinois Français, may be the earliest surviving Vietnamese–French dictionary and notably includes both quốc ngữ and Nôm. Organized hierarchically in the Vietnamese manner (e.g., sections on “Heaven,” “Mankind,” then “Animals”), it differs from Du Ponceau’s unannounced reordering in print and even contains a charming musical notation illustrating Vietnamese six tones with a well-wishing sentence to the captain. Copied by Father Morrone—likely drawing on unnamed Vietnamese teachers—the dictionaries map a network linking missionaries, merchants, and scholars. Their rediscovery underscores how, beyond Western collectors, Vietnamese interlocutors actively taught and shaped what outsiders came to know, and why these manuscripts continue to spark new conversations today.

Read the complete article here.