Author Q & A: Phi-Vân Nguyen Recounts the History of ‘A Displaced Nation’

A new Weatherhead Studies title untangles the many "conflicting and almost contradictory interpretations" of the 1954 relocation of more than 800,000 Vietnamese.

The 1954 Geneva Agreements that formally ended the First Indochina War also instigated the relocation of more than 800,000 Vietnamese from the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (the North) to the State of Vietnam (the South, or, as it would soon be known, the Republic of Vietnam).

A new title in the Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute series, A Displaced Nation: The 1954 Evacuation and Its Political Impact on the Vietnam Wars (Cornell University Press) by historian Phi-Vân Nguyen, situates this massive population transfer within a much longer chronology — a timeline that extends from Vietnam's 1945 declaration of independence through the end of hostilities with its neighboring states some 45 years later, at the close of the Cold War.

In telling the 1954 evacuees' stories across decades, Nguyen reveals them to be a much more heterogeneous group than they were often made out to be, whether by partisans on both sides of the North/South divide or by foreign governments with a stake in the conflict. A restive subset of the newcomers to South Vietnam thought of themselves as internal exiles; they were followed by a post-1975 generation of actual exiles, some of whom clung to the dream of regaining what they lost to the communist takeover while others in the diaspora eventually made their peace with the regime.

As Nguyen writes of these often-fractious communities, near the end of her book: “People wondered whether several Vietnams could coexist. For some, it became increasingly clear that there were multiple Vietnams that existed across political borders and interacted with one another.”

Phi-Vân Nguyen is Associate Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Science at the University of Saint-Boniface in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Via email, she answered our questions about A Displaced Nation.

Here in the United States, even people who assume they know something about the Vietnam conflict may be less familiar with the 1954 evacuation and its ripple effects. Can you briefly describe this event, and why it proved to be so consequential over the following decades?

Phi-Vân Nguyen: The evacuation happened when the Geneva Agreements temporarily divided Vietnam at the 17th parallel and assigned the north to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the south to the State of Vietnam. As a result of this ceasefire, the armed forces had a 300-day time period, starting July 21, 1954, to gather in the zone assigned to their political authority. But article 14d also allowed civilians to join the zone of their choice. By the end of this transitional period, over 800,000 people left the north to go to the non-communist zone in the south, whereas only 150,000 people went to the north.

This evacuation attracted a wave of solidarity because the Western world was moved by the fate the Vietnamese who fled the Communist regime in the north. This population movement had a significant impact, and not just because it was a lot of people to welcome and resettle on short notice. This wave of support boosted Saigon's legitimacy by giving the impression it enjoyed some popular backing. This worldwide backing also convinced a group of intellectuals and political leaders among the evacuees that the Western world would not leave Vietnam divided and the north under communist rule. Some had the impression that their own struggle to fight communist expansion, revert the partition, and return to the north would prevail in the future because of this widespread support. Surprisingly, this impression did not remain constant during the war but kept coming up over the following decades and even after many of them left overseas after the fall of Saigon.

In your essay in The Cambridge History of the Vietnam War, Volume I: Origins, you write: “The adoption of global approaches to the history of the Vietnam Wars has enabled a new focus on multidimensional, multi-institutional, and longue durée connections.” Tell us how your account of the 1954 evacuation and its consequences benefits from some of those connections.

Nguyen: The idea of longue durée generally applies to a very long time frame, a near immobile history, which contrasts with an event or economic or political cycles. But in the context of the Vietnam wars, it refers to the historical processes and dynamics which develop or build up over a time that is longer than a battle, a military campaign, a presidential administration, the implication of a belligerent (France, or the United States). The longue durée refers to processes that often run across the three Vietnam wars, or connect them to the Pacific War, or the earlier process of decolonization.

In A Displaced Nation, I try to show that the Vietnam wars were not just three separate armed conflicts: a war of decolonization against the French (1946-1954), a war of unification (1959-1975), and a war opposing Communist brothers when Vietnam fought against its two neighbors, Cambodia and China (1978-1989). It was also a continuous war opposing Vietnamese to each other about what the postcolonial country should become.

Shifting the chronological limits and subject of study also opens our horizons. We don’t only see the continuities between these armed conflicts: Looking at the evacuation also allows us to see the wide range of transnational connections intersecting in Vietnam and how people and ideas circulated across these networks during the wars. The evacuation, for example, shows that the Vietnam wars were not only a war of decolonization, a frontline of the Cold War, or a civil war opposing Communist to Nationalist parties. For many members of the Roman Catholic church, this was also a struggle to protect freedom of religion, determine the role of the Catholic faith in a democracy, and define the composition and orientation of the Church in postcolonial Vietnam.

Above: Vietnamese evacuees board the amphibious U.S. Navy vessel LST 516 for their journey from Haiphong, North Vietnam, to Saigon, South Vietnam, during Operation Passage to Freedom in October 1954. (U.S. Navy photo / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

In this history, names matter, as the same population is referred to, at various times and by various sources, as “evacuees,” “migrants,” and “refugees.” (And that’s even before we reach the “boat people” of the next generation.) Why are these different terms important?

Nguyen: The 1954 evacuation was important to many people, but this same population movement meant something different for them. From the perspective of the United States, the people leaving the north were victims fleeing persecution. This interpretation allowed the United States to imply that Hanoi was a threat to its own population. So, this was one way to continue the war by other means after the ceasefire. Yet it implied that these refugees would find solace once resettled in a safe place. Most Vietnamese-language documents and newspapers back then, however, referred to the people leaving the north as migrants because many intellectuals and political leaders among the evacuees rejected the idea that they were victims and insisted that their departure was temporary. They were convinced that one day, they would return to the north.

Interestingly, the State of Vietnam and later the Republic of Vietnam, as well as many of these evacuees, realized that there were conflicting and almost contradictory interpretations of the evacuation. But they chose to entertain that confusion because this was the best way to capture the attention and support of the Western world.

This compromise is in fact revealing of a larger problem. The coalition of states and people who joined their forces in the fight against communist expansion did so for different reasons. The United States wanted to stop communism at the 17th parallel and Saigon wanted to build a strong Republic in the south. Yet many evacuees wanted to continue the war and free the north from communist rule. So, Washington, Saigon, and the evacuees fought together. But they had ultimately different war goals.

Your work builds to a poignant finish as you write: “The end of the Cold War ultimately led many evacuees to acknowledge that the Vietnam of their imagination would never exist within the borders they envisioned. Vietnam would continue to exist across continents.” I wonder if you can expand a little on this idea of a country that transcends geographic and political boundaries—and what it might look like in 2025, 50 years after the end of the American war.

Nguyen: For a very long time, we saw the Vietnam wars as a long fight for the making of a nation-state. However, the armed conflict has produced large population movements. Sometimes alternative visions of the nation-state traveled abroad with these people and the hope that some entertained of returning to Vietnam even revived during the Third Indochina War. These projects have shifted since the end of the war but the disconnect between different visions of the nation-state has remained.

The opening of Vietnam's borders since 1986 has increased the opportunities for Vietnamese to travel and families to reunite. Vietnamese living overseas have come back to the country to visit, work, or retire, and people from Vietnam have left the country to study, work, or live abroad. Yet the circulation of goods and ideas, along with this movement of people, has not reinforced one unique vision of the nation-state. In fact, 50 years after the end of the war, Vietnam refers to both a country of origin that is common to all these people and a diaspora scattered across the globe.

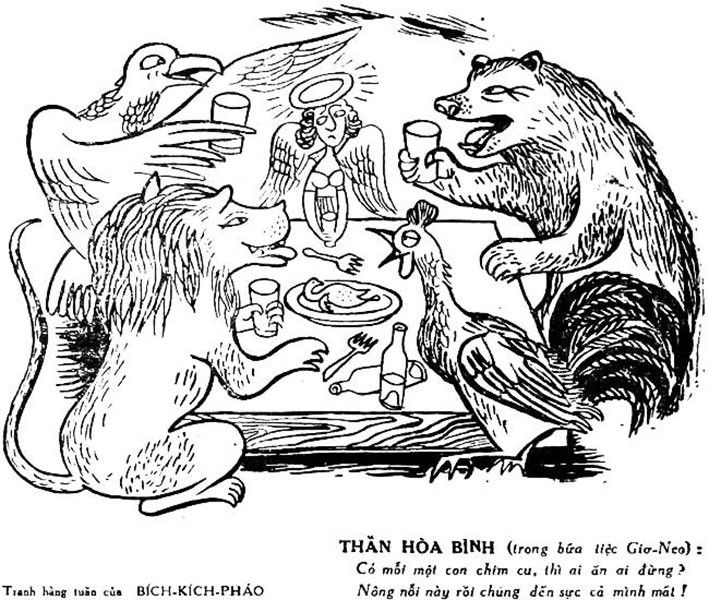

This August 1955 political cartoon by Bích Kích Pháo satirizes the division of Vietnam by foreign powers. The Russian bear and French rooster feast, the British lion and American eagle are eager to partake, and the tiny Vietnamese dove lies in the center of the table as the Angel of Peace looks on uneasily. This image is reprinted in Phi-Vân Nguyen's A Displaced Nation: The 1954 Evacuation and Its Political Impact on the Vietnam Wars.

By Jeff Tompkins

December 03, 2025