Digitizing Việt Nam marks a digital leap forward in Vietnam Studies through a Columbia - Fulbright collaboration, formalized through that began with a 2022 memorandum of understanding between the Weatherhead East Asian Institute and the Vietnam Studies Center. The Digitizing Việt Nam platform began with the generous donation of the complete archive by the Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation to Columbia University in 2018.

Delve into Vietnam's history, culture, and society through cutting-edge tools and curated resources tailored for scholars, students, and educators.

Explore our digital archive dedicated to preserving and academically exploring Vietnam's historical, cultural & intellectual heritage.

Engage creatively with Vietnam Studies — Use Digitizing Vietnam's specialized tools to approach the field with fresh perspectives and critical insight.

Discover and teach Vietnam Studies with impact — Explore curated syllabi, lesson plans, and multimedia resources designed to support innovative and inclusive learning experiences.

Latest news and discoveries from the digital front of Vietnamese heritage.

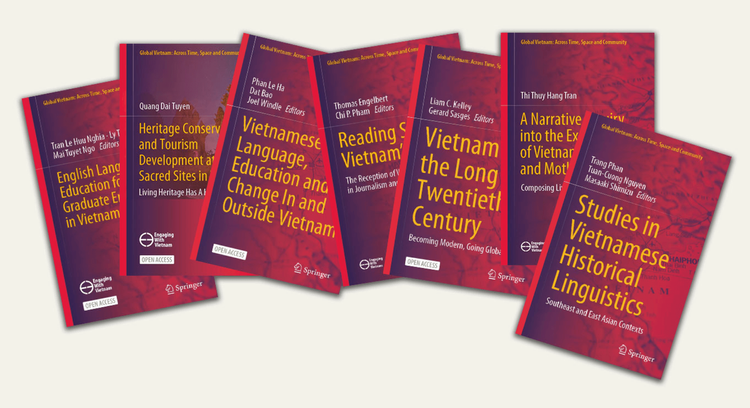

Edited by Phan Lê Hà and Liam C. Kelley, the book series Global Vietnam: Across Time, Space, and Community is devoted to advancing scholarship on Vietnam and Vietnam-related questions while fostering a new generation of scholars working in the arts and humanities, education, social sciences, and interdisciplinary fields. It situates Vietnam within global contexts and explores “global Vietnam” across time, space, and diverse communities.

The series brings together original research and fresh interpretations that attend to the nuances, complexities, and ongoing transformations that Vietnam—in all of its possible meanings and constructions—has inspired and generated. It also recognizes the expanding global networks of Vietnamese and Vietnam-focused scholars whose work reflects a contemporary moment in which knowledge production is increasingly decentralized and transnational. These intellectual commitments have been cultivated over more than a decade through the Engaging With Vietnam conference series, from which this book series has grown as a natural extension.

To date, the series includes the following volumes:

1. Research and Teaching Vietnamese as a Second Language: A Global Perspective (2026), edited by Trang Phan and An Sakach.

2. Living with Heritage in Contemporary Vietnam (2026), edited by Stan BH Tan-Tangbau, Phạm Quỳnh Phương, and Trần Thị An.

3. Race, Resilience, and Vietnamese Americans in New Orleans: The Unmaking of Home (2025), by Nguyen Vu Hoang.

4. The Making of Intellectual Property Law in Vietnam: From Colonial Laboratory to Socialist Legality, 1864–1994 (2025), by Tran Kien.

5. Vietnam Over the Long Twentieth Century: Becoming Modern, Going Global (2024, open access), edited by Liam C. Kelley and Gerard Sasges.

6. Heritage Tourism: Vietnam and Asia (2025), edited by V. Dao Truong and David W. Knight.

7. Vietnamese Language, Education and Change In and Outside Vietnam (2024, open access), edited by Phan Lê Hà, Dat Bao, and Joel Windle.

8. Vietnam’s Creativity Agenda: Reforming and Transforming Higher Education Practice (2024), edited by Catherine Earl.

9. Studies in Vietnamese Historical Linguistics: Southeast and East Asian Contexts (2024), edited by Trang Phan, Tuan-Cuong Nguyen, and Masaaki Shimizu.

10. A Narrative Inquiry into the Experiences of Vietnamese Children and Mothers in Canada: Composing Lives in Transition (2023), by Thi Thuy Hang Tran.

11. Reading South Vietnam's Writers: The Reception of Western Thought in Journalism and Literature (2023), edited by Thomas Engelbert and Chi P. Pham.

12. Heritage Conservation and Tourism Development at Cham Sacred Sites in Vietnam: Living Heritage Has a Heart (2023, open access), by Quang Dai Tuyen.

13. English Language Education for Graduate Employability in Vietnam (2024, open access), edited by Tran Le Huu Nghia, Ly Thi Tran, and Mai Tuyet Ngo.

Together, these volumes illustrate the breadth of themes, disciplines, and methodological approaches that define the series, reflecting Vietnam’s entanglements with regional and global processes as well as the vitality of contemporary Vietnam-focused scholarship.

For more information, visit:

https://link.springer.com/series/17025/editors

Columbia University Libraries proudly unveils the Vietnamese Hán-Nôm Digital Collection, an exceptional digital archive of approximately 1,100 rare and invaluable texts drawn from the Hán-Nôm holdings of the National Library of Vietnam, Thắng Nghiêm Temple (Hà Nội), and Phổ Nhân Temple (Hưng Yên).

At the heart of this collection is a remarkable preservation effort led by the Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation (VNPF), which, together with the National Library, digitized these works to safeguard Vietnam’s literary and intellectual heritage. Spanning the premodern to early modern eras, the texts illuminate a vast spectrum of knowledge, from literature, history, and geography to religion, medicine, musicology, folklore, and general science, all recorded using the Hán - Nôm script.

Following VNPF’s completion of its mission and dissolution in 2018, the collection was acquired by Columbia University Libraries in 2021. Today, the Libraries steward the archive in collaboration with the Digitizing Việt Nam Project, an ongoing initiative carried out by the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University in collaboration with the Vietnam Studies Center at Fulbright University Vietnam, dedicated to supporting access, tools, and scholarship for students and researchers of Vietnamese studies worldwide.

View the collection here: https://dlc.library.columbia.edu/npf_vietnamese

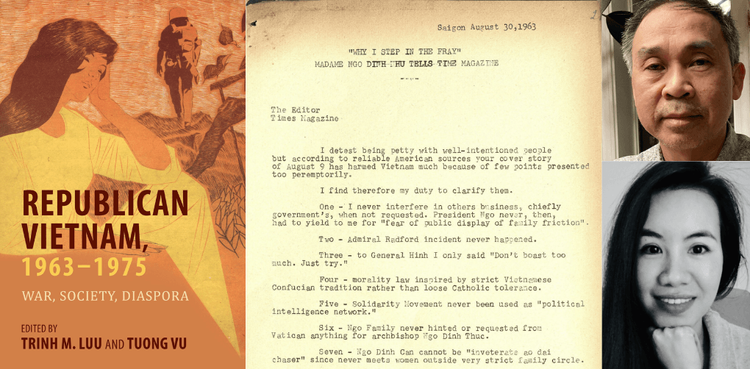

English-language scholarship has too often reduced South Vietnam to a mere American fabrication, portraying it as little more than an outgrowth of U.S. imperialism. As another title amongst the series Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University, Republican Vietnam, 1963–1975: War, Society, Diaspora (University of Hawaii, 2025), edited by Trinh M. Luu and Tuong Vu, decisively challenges this view by revealing the Second Republic as a diverse, dynamic, and internally driven society. Across twelve essays grounded in original archival research, the volume reconstructs the Second Republic in all its complexity, showing how politicians, students, educators, publishers, journalists, musicians, religious leaders, businesspeople, and ordinary citizens together forged a richly layered social world. This society was marked by remarkable entrepreneurial energy, a combative and outspoken press, globally connected religious institutions, a vibrant intellectual and associational life, and a level of artistic production unparalleled since the Vietnam War.

Although this period was brief, its intensity and creativity fostered a resilient republican spirit that Vietnamese refugees later carried into exile. The abundant legacy of vernacular music, print culture, and the many associations established by the Vietnamese diaspora attest to the republican values that once animated South Vietnamese life. Yet despite this complexity, popular media and much American scholarship have continued to depict South Vietnam as a fundamentally dependent polity, ruled by corrupt leaders beholden to U.S. interests. Against such reductive portrayals, this volume places South Vietnamese actors at the center of their own history, emphasizing their agency, aspirations, and struggles.

Republican Vietnam is the first scholarly collection devoted to the Second Republic to appear since the end of the Vietnam War, and among the earliest to employ republicanism as an analytical lens for reexamining twentieth-century Vietnamese history, the war itself, and the Vietnamese diaspora. Taken together, the essays demonstrate how warfare, intertwined with foreign intervention, shaped South Vietnam’s economy, culture, and the everyday lives of individuals and families. By bringing together scholarship from both Vietnam-based and diasporic studies, the volume bridges two fields that have long developed in parallel, laying essential groundwork for future cross-disciplinary research.