Article Published in Tuổi Trẻ Newspaper, February 2, 2025

Vietnamese cinema history records its first-ever film produced exactly 100 years ago: Kim Vân Kiều, an adaptation of Nguyễn Du’s Truyện Kiều, co-produced by Vietnam and France and screened in Hanoi in 1924.

Despite conflicting reviews from contemporary newspapers, the film reflected a growing desire to assert national identity and cultural values through “modern” media amidst the influence of Western civilization.

Though the film has been lost, a few rare photographs remain, and 21st-century enthusiasts are striving to revive it using digital technology and artificial intelligence (AI).

Kim Vân Kiều on the Silver Screen

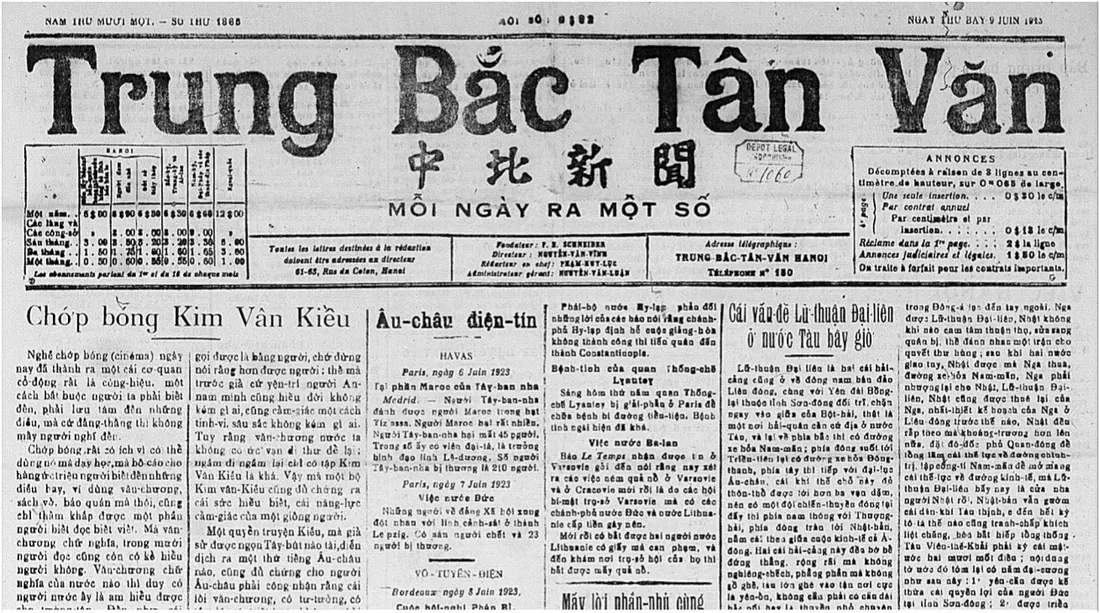

Readers of Trung Bắc Tân Văn on June 9, 1923, may have been surprised to see a front-page article by the newspaper’s publisher, Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh, titled Chớp bóng Kim Vân Kiều (Kim Vân Kiều on Film).

At that time, cinema was only 33 years old globally, and Hanoi’s first movie theater—built by the French—had been open for just three years, following years of screenings in French government buildings and military barracks.

Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh began his article by emphasizing the importance of cinema in the modern world:

“Cinema has become an extremely effective means of propaganda, forcing people to pay attention to things they might otherwise overlook.”

He saw cinema as an educational and communicative tool beyond written language, using “moving images” to evoke universal emotions and understanding across borders.

Because of this accessibility, great literary works, philosophical ideas, and artistic masterpieces—once reserved for an intellectual elite—could now be widely shared with the public, becoming both a “pleasure for the mind” and a means of mass enlightenment.

By advocating for Truyện Kiều’s adaptation into film, Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh initiated a dialogue on cultural modernization, challenging the colonial claim that Western civilization had a “civilizing mission” in Vietnam.

From Literature to Film: National Pride

Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh pointed out that Europeans and Americans took pride in their literature and intellectual heritage, seeing it as proof of their superiority over Asian cultures. However, in Vietnam’s literary tradition, Truyện Kiều stood as undeniable evidence that the Vietnamese were not an “inferior race.”

He argued that Nguyễn Du’s work demonstrated Vietnam’s depth of thought, psychology, and philosophy, proving that literary sophistication was not exclusive to the West.

For Vietnamese intellectuals of the 1920s—who had endured nearly two decades since the suppression of the Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục movement (1907–1923)—the national pride in Truyện Kiều was a response to colonial claims of cultural superiority.

This sentiment was echoed by Phạm Quỳnh, who, at the Nguyễn Du commemoration organized by Hội Khai Trí on September 8, 1924, famously declared:

“As long as Truyện Kiều exists, our language exists—if our language exists, our nation exists.”

Understanding cinema’s power in the modern era, Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh saw film as the ideal medium to promote Truyện Kiều domestically and internationally. He had already translated Truyện Kiều into French, publishing it in Indochina Magazine (beginning in issue #18), and the presence of Indochine Film in Hanoi made his vision of a film adaptation increasingly viable.

His collaboration with Indochine Film was thus the convergence of two ideas—the recognition of Vietnamese intellectual heritage and the potential of cinema to amplify it worldwide.

“A Token of Faith Remains…”

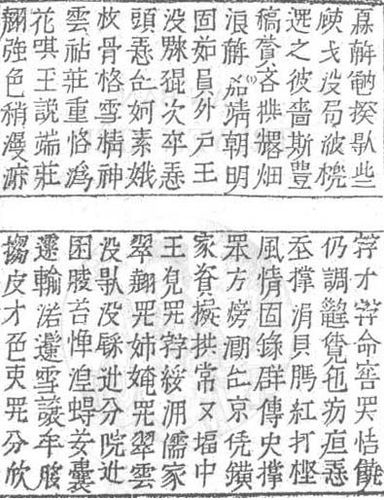

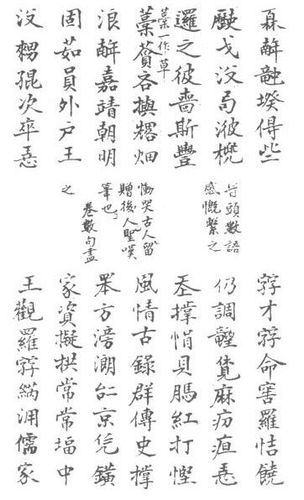

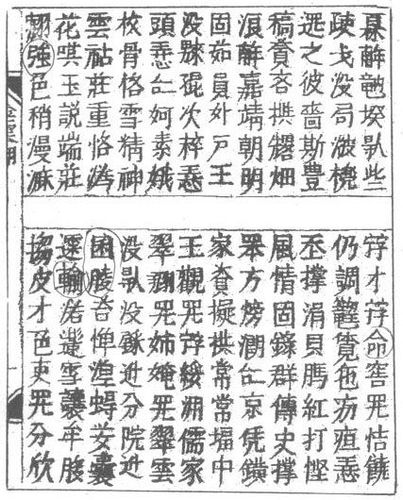

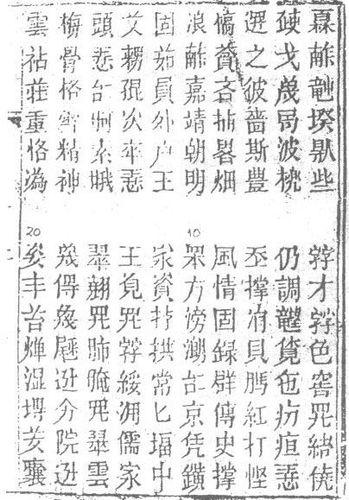

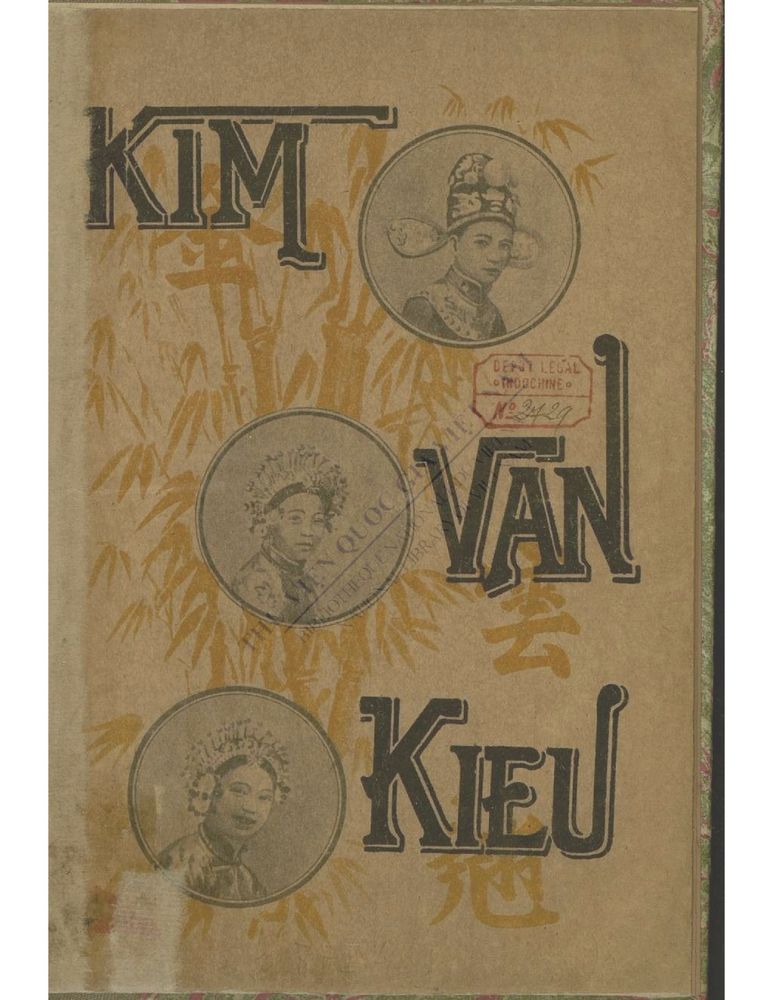

The book Kim Vân Kiều (7th edition, 1923) was transcribed into quốc ngữ (Romanized Vietnamese) and annotated by Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh.

Though written in Vietnamese, Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh’s articles caught the attention of French readers, particularly those involved in the Kim Vân Kiều film project.

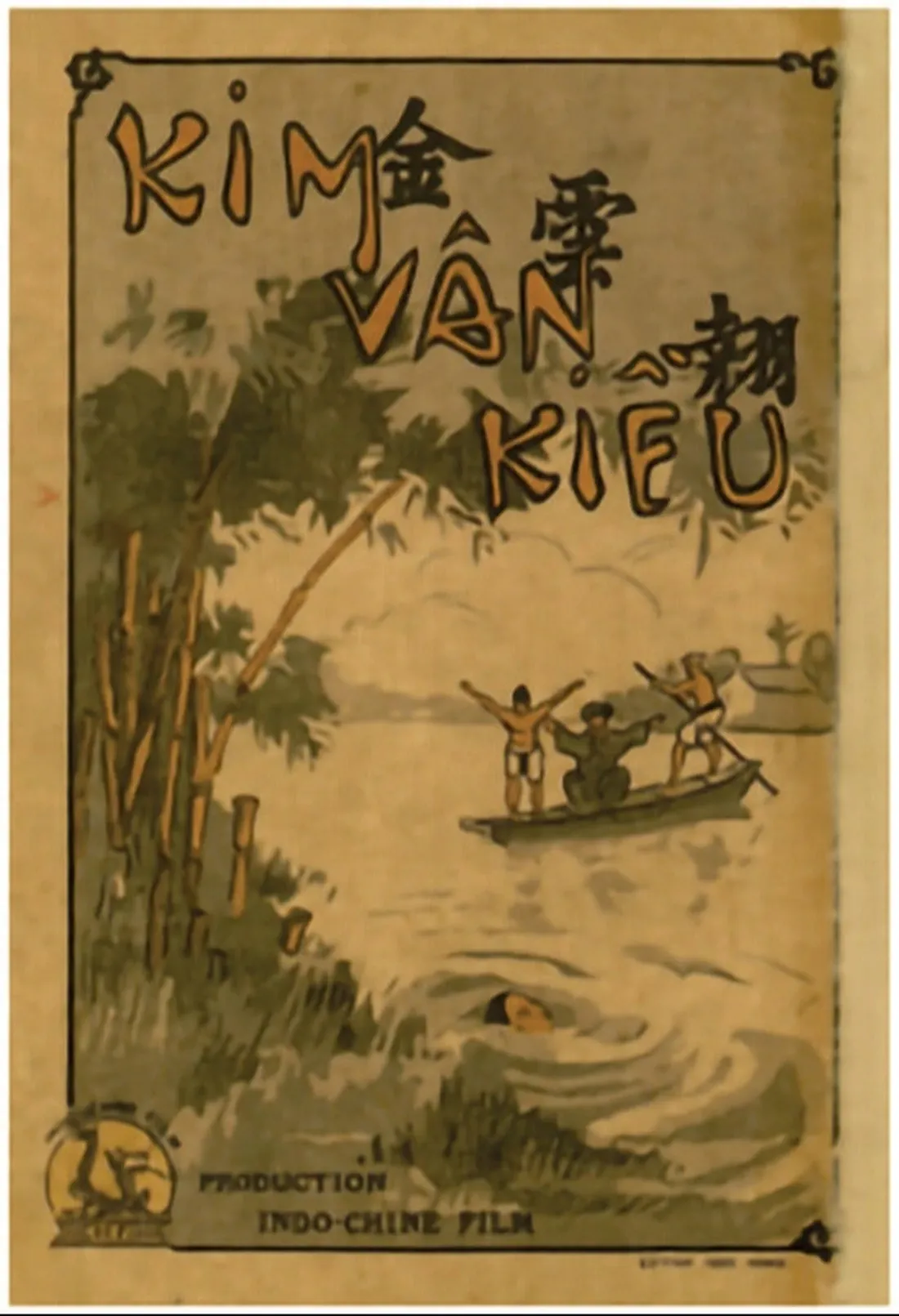

In early 1924, Thái Bình Dương magazine published a letter from the Indochina Film & Cinema Company (IFEC) titled Le Cinéma Indochinois (Indochina Cinema), revealing that the idea of adapting a local novel had emerged a year earlier during the Colonial Exhibition:

“The idea of filming an indigenous novel first came to us last year at the Colonial Exhibition. We do not want to be among those who produce colonial novels without understanding a single word about the actual life of the colonies.”

Today, a rare booklet titled Kim Vân Kiều, published by La Société Indochine-Films & Cinémas after the film’s release, still survives. It contains a short introduction in Vietnamese, while the remaining articles are in French.

However, the introduction begins with the line:

“Thúy Kiều, daughter of Vương Viên Ngoại, lived in Beijing, China.”

This explains why the film’s costumes, a blend of styles rather than purely Vietnamese, were criticized by Chinese-language newspapers like Đông Pháp Thời Báo.

The publication also revealed the filmmakers’ philosophy: the adaptation had to suit the cinematic medium, emphasizing emotional impact over strict adherence to the original text. They believed that a successful film should move audiences to tears, making them truly feel the story’s tragedy.

Thus, despite its historical limitations, the Kim Vân Kiều film and its subsequent publication marked an early effort to bridge literature and cinema, preserving Vietnam’s cultural identity in an era of colonial influence.

In 1923, in his article in Trung Bắc Tân Văn titled “A Cinematic Adaptation Of Kim Vân Kiều,” Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh imagined Kim Vân Kiều as a medium to capture the depth of the Vietnamese psyche through cinema—an art form introduced by colonial forces. The film, like the story it adapts, is marked by encounters, separations and reunions. Being Vietnam’s first film, Kim Vân Kiều (1924) represented an unprecedented marriage between Vietnamese literature and European cinematographic technology, a work then lost to time and later reconstructed—much like the turbulent connection between Kim and Kiều. Though now lost, the surviving stills from the film, preserved in a book published later by La Société Indochine Films & Cinémas, remain as evidence of Vietnamese cultural resistance against colonial dominance. By suturing these AI-restored fragments in slow cinema, we create a space-time for an encounter between past and present. This ephemeral connection parallels the story of Kim and Kiều, as viewers today engage with the film’s spectral presence, longing for meaning in what’s left and thinking about what could have been. Much like the fleeting encounter between Kim and Kiều, foreshadowing an inevitable separation, our interaction with this lost film is similarly fragile, leaving us to wonder:

“Now we meet, face to face at last,

Who knows if it’s not soon a dream from the past?”